Why High-Speed Rail Has Failed

Throughout the 80’s and 90’s, a steady stream of elected officials and bureaucrats made their way to Japan. I don’t know what happened on these trips, or why they were taking them, but I do know that many of them left impressed with one thing in particular: Japan’s Shinkansen network, a system of high-speed trains in the island country. The Shinkansen snaked through the country’s mountainous terrain and various islands, transporting passengers in a way that America had never seen before. Yes, America had trains and planes. Still, there was an underserved market that high-speed trains could fill: trips a few hundred miles long that were too long for traditional trains or cars but too short to justify a commercial flight. So, when those elected officials and bureaucrats returned to the United States, they surmised to bring the Shinkansen to America.

Before the Shinkansen inspired American officials, the United States had already tried its hand at faster rail service: the Metroliner. It was an all-electric train meant to operate between New York and Washington D.C. at a speed of 150 miles per hour. Spearheaded by the LBJ administration, the Metroliner was a private-public partnership in an era when America’s passenger rail travel was still a private endeavor. The government’s role would be to provide financial assistance to assist private companies in acquiring the trainsets. But as the launch date approached, these companies were struggling to get the trains operational. The rollout of the Metroliner required extensive investment to electrify the tracks and extend the platforms along the route to accommodate the longer trains. These investments were far from cheap, causing the original Metroliner operator, Pennsylvania Railroad, to collapse and fold into a competitor before the launch. Even consolidation could not save the Metroliner’s original vision, and the Metroliner’s top speed was reduced from 150 mph to just 110 mph due to infrastructure constraints, and the service was launched a year late. The Metroliner went onto public acclaim despite the chaos. The rough rollout of the Metroliner would be far from the worst American rail would see.

In 1991, President H.W. Bush signed into law the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act. The bill was broad: it created the rail to trails program, mandated airbags in passenger vehicles built after 1998, and designated five different potential high-speed rail corridors in America, including the Northeast Regional corridor.

Up until this point, Amtrak had been running the Metroliner for nearly thirty years and speeds still had never reached their original goal. So, using its new federal funding, Amtrak called for proposals of a new high-speed train that might live up to the original promise of the Metroliner: Acela. Acela would look like a high-speed train of Europe or Asia. It would tilt into curves like other high-speed trains, a necessity along the windy Northeast corridor. Acela would be able to travel between Washington and Boston on electric-only, unlike the previous service that terminated in New York. Finally, and most importantly, Acela would surpass the Metroliner’s speeds at the time. Amtrak required bids to be able to build a train capable of hitting speeds of 165 mph. The promise of American high-speed rail had been renewed. But these specifications, along with the requirement that Acela be able to withstand impact from a freight train, sent costs skyrocketing.

With reality setting in and costs skyrocketing, so too was the promise of Acela downgraded. Sharing tracks with traditional trains meant congestion and expensive designs to accommodate both trains. The infrastructure itself was very old, as the bridges and tracks could not handle a 620-ton trainset barreling over them at 165 miles per hour. Neither could the people living next to the tracks, whose homes had been built decades prior, without high-speed train noise considerations in mind. Local regulations were erected to limit Acela’s speed through their neighborhoods, and the federal government restricted the train’s speed over aging infrastructure. This meant that Amtrak’s marquee service would take 2:45 to travel at an average speed of 82.2 miles per hour between Washington, D.C. and New York, a speed slower than even the fastest Metroliner times decades prior. Acela was relegated to an aesthetic improvement over its predecessor.

This would not end America’s foray into high-speed rail. One of those elected officials in the 80’s traveling to Japan was Gov. Jerry Brown of California, who after returning from a trip decided that his state needed high-speed rail as well. But having decided to not seek a third term (yet), time was not on the governor’s side. All he could pass before leaving office was a feasibility study that began the state’s foray into the complexities of bringing high-speed trains to the state. Little did anyone know that it in 29 years, he would be back in the governor’s office picking up nearly exactly where he left off.

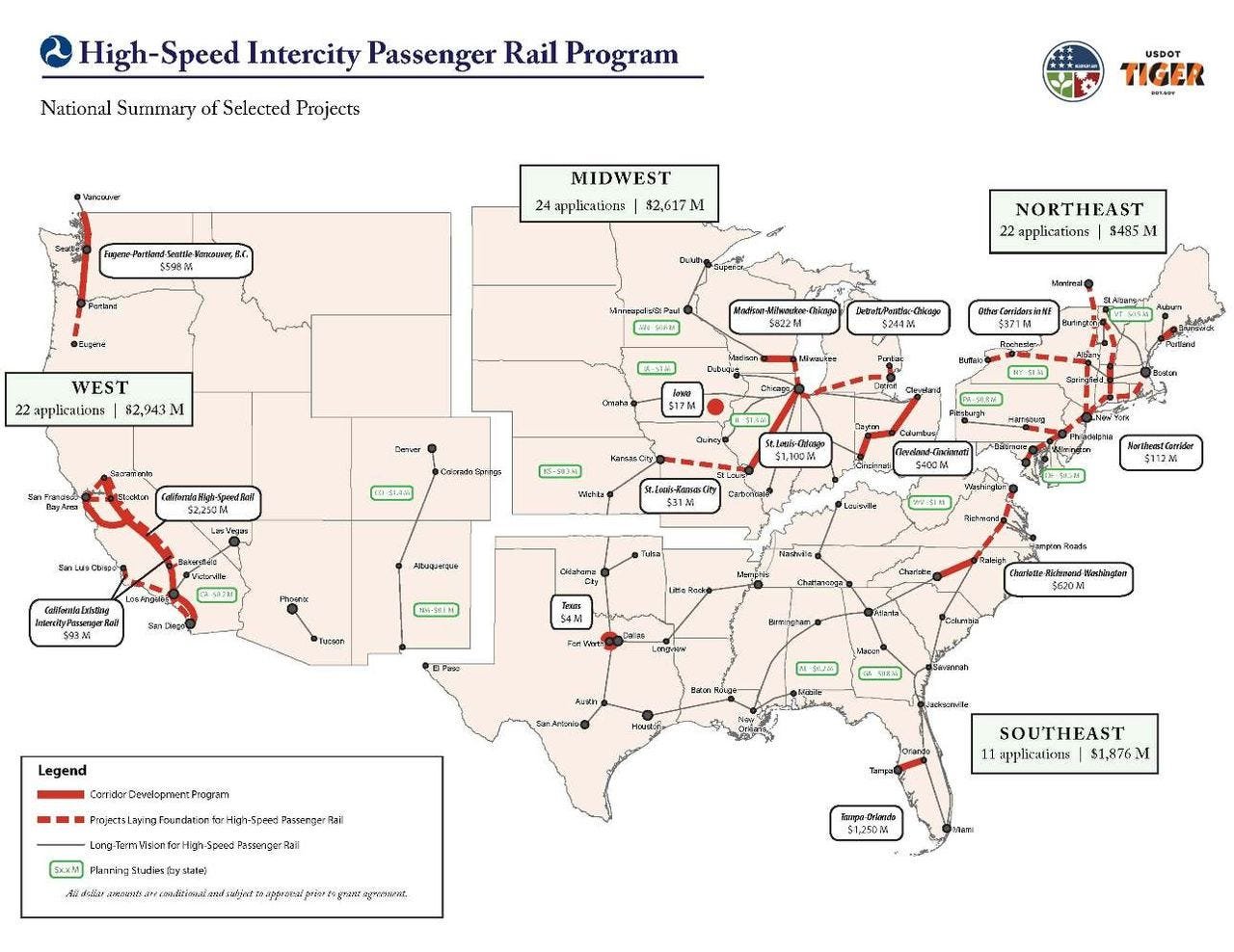

Back as governor in 2011, Jerry Brown declared, “I would like to be part of the group that gets America to think big again.” In the time between his first and second stint as governor, not much had happened regarding the development of high-speed rail in the state. A high-speed rail authority was set up which didn’t seem to amount to much of anything in the 15 years it existed. Cost projections were released that pegged the cost of connecting San Francisco and Los Angeles by rail at $25 billion. Most notably, Brown’s predecessor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, was able to get a high-speed rail bond initiative on the ballot. It passed, allowing the state to raised up to $9.95 billion for high-speed rail projects in the state. Federal funds in the wake of the Great Recession were also in the coffers.

But with nothing to say for the project, the cost was already rising. The original plan called for true high-speed rail: exclusive tracks running from San Francisco to Anaheim, with a sustained top speed of 220 miles per hour. This was projected to cost $33 billion dollars, up already from the original projection of $25 billion. Even that projection was short-lived. The rail authority realized that the cost of running the system on exclusive tracks was far from cheap: it would triple the cost of the project to $98 billion. So just like Acela, expectations started being cut back: the authority opted to share tracks with commuter trains in the Bay Area, requiring a second door on each railcar to accommodate two different platforms heights. This compromise was not enough: along with other complications, the cost still remained twice as high as the most recent projection: now $65 billion.

Then the project hit more, but predictable, roadblocks. Land acquisition (through eminent domain) became lengthy and costly. County governments sued the state government. Consultants overpromised and underdelivered (ever heard of that happening before?), capturing roles that should have been filled by the government. Environmental reviews were required ad nauseum. Politicians and constituents alike were angry that they didn’t get their specific carveout, with one Republican Councilmember even spending $3,000 to complain that the high-speed rail money should be used to build a dam instead.

These issues plagued Gov. Brown throughout the entirety of his second stint in office. So even though the project broke ground before he left office, but Brown didn’t have much to show for eight years of effort. To add insult to injury, after leaving Sacramento, the price jumped by $10 billion and the cumulative delay became 13 years. California’s new governor Gavin Newsom canned the project. Though it was less so a cancellation, and more so an “indefinite postponement” of the most essential portions of the project: the tracks around San Francisco and Los Angeles. Newsom kept the portion of the project to build 163 miles of track between Merced and Bakersfield alive, a far cry from the original ambition to connect California’s two population centers.

So, why has high-speed rail failed every time it has been tried in the United States? It is not for a lack of effort or a lack of money. You’d think that after decades of head-banging that our public officials would find at least some progress past the obstacles that have stood in the way. What gives? It is a complex system of factors which can be grouped into two buckets: legal and structural.

The legal obstacles in opposition to high-speed rail may have had benevolent intentions when first passed, but are lethal to any aspiring high-speed rail project. Environmental reviews make construction an expensive endeavor before shovels even start moving dirt. Sturdy property rights make the acquisition of privately owned land expensive and lengthy: a problem that countries like China don’t face. A culture of public input makes every inch of track an issue worthy of public hearings and comment. Contractors and their unions know all too well how to extract money from public entities who don’t know any better to turn the tap off. These are problems so large that they cannot be solved by any transit authority alone; they are deeply ingrained local, state and federal laws that breed a culture of that demands too many cooks in the kitchen. The result is the accumulation of cost overruns and delays that kill once-ambitious projects.

The problems are also structural, geographically and historically speaking. American advocates of high-speed rail don’t realize how little density America has compared to other countries with high-speed rail. For example, the route between San Francisco and Los Angeles would have been nearly 440 miles long, compared to the 238 miles between London and Paris. Tokyo to Osaka is 320 miles. Generally, high-speed rail with multiple stops is only practical under distances under 500 miles. California’s main route pushes this limit, with nothing to say on other ambitious proposals that call for a national high-speed rail network.

Then in a place like the Northeast Corridor, why haven’t we seen true high-speed rail? The distance from New York to Washington is about the same distance from London to Paris, right in the sweet spot. The answer here is one of space, and one that beckons to the legal concerns listed above: where are we going to put this track? Much of the existing rail in the Northeast corridor is abutted by industry, homes, and cities. Seventy years ago, building on greenfield would have made this a non-issue. But with suburban sprawl, acquiring all this property would be a monumental task, costing untold billions of dollars and disruption. When the systems of Europe and Japan were built, they did not nearly have this problem. They built high-speed rail, alongside a culture that valued it, well before infrastructure glut could get in the way. Status quo bias is a hell of a phenomenon.

So, the case against high-speed rail is not a case against high-speed rail itself. On its face, high-speed rail is a wonderful idea. It is a (potentially) green alternative to driving or flying and provides travelers with the opportunity to travel from downtown to downtown rather than to airports on the periphery. Instead, the case against high-speed rail it is a feasibility argument. It is an argument against the complex systems that prevent high-speed trains from taking to the tracks. If it were feasible to overhaul our burdensome environmental reviews, pump out corruption from our infrastructure contractors, reform the legal incentives that encourage public resistance to high-speed rail, demolish our current infrastructure without quality-of-life concerns and move our cities closer together all at once, then high-speed rail would be a no-brainer opportunity. Even reform in just a few of these areas might put high-speed rail over the edge.

But I’m not holding my breath for these structural concerns to be addressed. So, what are the solutions? For one, we can invest in our existing regional rail networks that connect suburbs to urban areas. Not only does this infrastructure already exist, but it is also far cheaper to build upon than to build high-speed rail networks from the ground up. Even urban metro systems, despite their cost, also have a clearer benefit than high-speed rail.

For long-distance trips, the U.S. can expand the Essential Air Program, coupled with carbon neutrality. The Essential Air Program subsidizes flights from small rural communities to large hubs so that people in those communities have access to the outside world. The program costs $290 million per year. For reference, the U.S government spent $450 million to upgrade 23 miles of signals in the Northeast corridor between Trenton and New Brunswick. This upgrade allowed trains to travel 25 miles per hour faster between the two cities.

And if we decide that we want high-speed rail in this country, we must be comfortable with rail authorities that have the power to build at their own whim. If on one end of the spectrum is the infrastructure paralysis that we are currently caught in, and on the other end is a figure like Robert Moses, then we need to carve out a middle ground between these two positions. The middle ground between these two positions is one where a powerful governmental authority can control costs and move dirt without requiring several environmental studies and public comment, but also cannot steamroll minority communities and destroy the landscape with impunity.

The problem with high-speed rail is not high-speed rail itself. With a desire to ride of 67%, Americans clearly desire a transportation alternative to our current offerings. It is a legal and structural problem. It is a problem that cannot be addressed by sheer will to simply lay down electrified track. It is a problem that requires shifting American culture away from feckless incrementalism and distrust of our political institutions to one that values change and visionary institutions that are willing to take risks to make the country a better place to live. Until then, the billions spent on high-speed rail are for a pipe dream best left to our counterparts in Europe, China, and Japan. That is for now, at least.